A timeless artwork radiates undeniable excellence, along with a mysterious potency. It has a unique freshness embodied within it that is enduring, remaining as vibrant as the day it was made. Such works are the design of genius; equal parts of the extraordinary - skill infused with distinct ideas. They are the result of a wonderful co-creative procedure in which the artist and the universal spirit merge into one creative and harmonic force.

Rich in an essence that allows us to be free from the physical and transcend above it – timeless art connects with and touches the soul. Sometimes, such works and their creators remain on the periphery of the art world, misunderstood and undervalued; they somehow remain unrecognized.

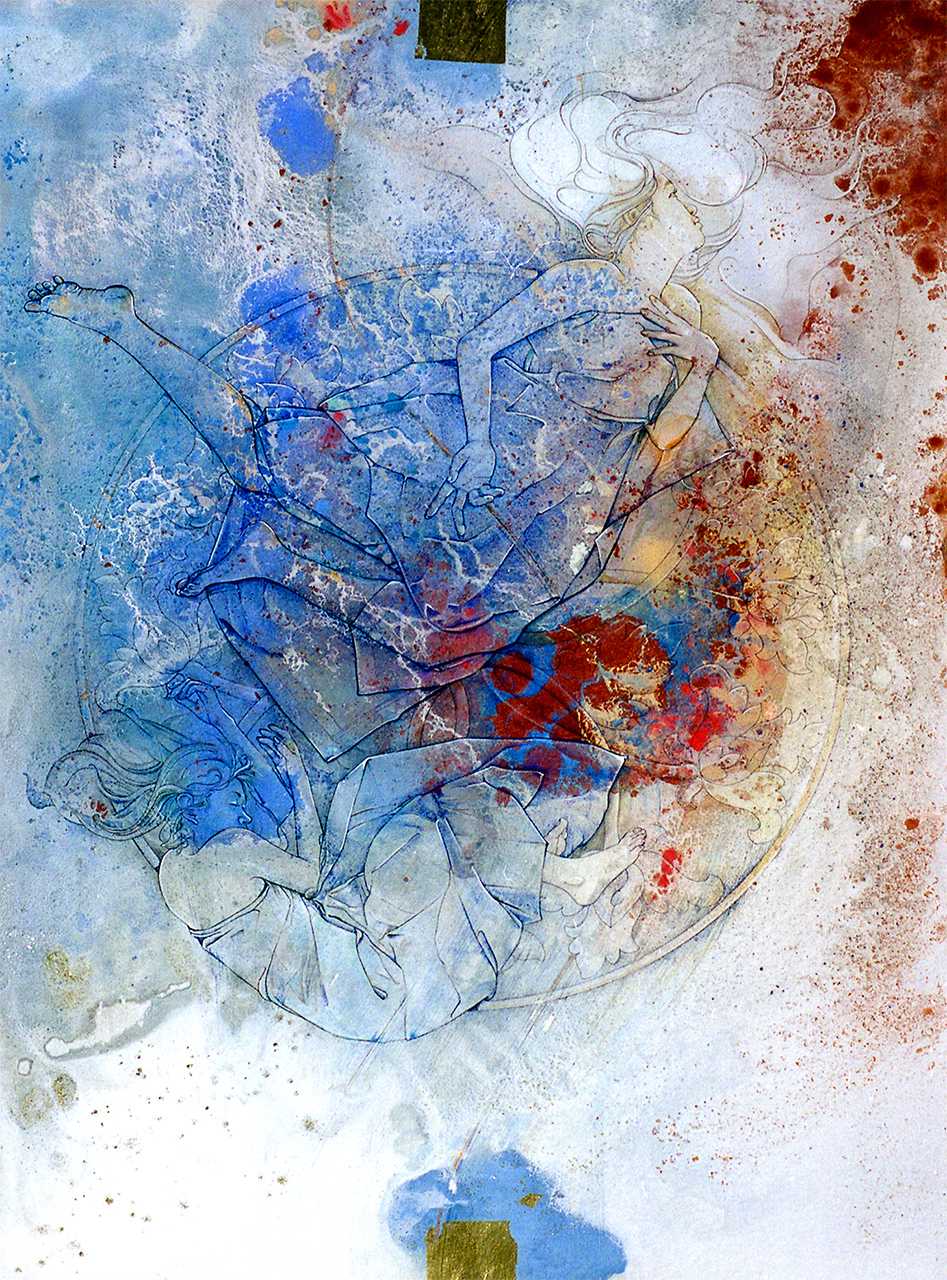

Jean-Philippe Haure is one such artist. A sensitive and gentle being his prowess comes alive in magnificent paintings that combine vibrant abstract backgrounds with meticulous drawings of the human form. At a glance, his compositions may appear confusing, and difficult to decipher – the visual matrix we engage in is indeed unfamiliar, being almost contradictory. Yet within the aesthetic milieu Haure depicts the human condition in a manner that is uniquely his own. His creative ‘voice’ defines him as one of the most talented expatriate artists to ever live and work in Bali.

Haure skilfully positions two visual worlds side-by-side, contrasting elements that represent distinct opposites; one of realism, and the other of make-believe. His colourful dynamic backgrounds present countless possibilities in our quest to bring meaning to their non-descript forms. Yet by placing these two opposing fundamentals together, the artist underlines his intention – to make a clear distinction between what is fantasy, and what is a reality.

Bali, Indonesia

Orientalism is a term not overly associated with the western artistic representations of Bali made during the last century, more so it is connected with the Asian continent. The prejudiced outsider-interpretations of Bali, its culture and people, are shaped by the attitudes of European imperialism and are the foundation of the exotic artistic interpretations of Bali. These visual ideas are based upon preconceived discriminating notions that are limited, and intentionally create an emotional barrier between the subject, which becomes an object, and the audience.

Haure’s intention is in opposition to this. He goes beyond the preconceived differences to reveal the human qualities within his subjects so that we may develop an emotional connection. We may then reflect upon their condition while addressing our similarities. Haure rejects the stereotypical images from the past century that predominate our thinking about the Balinese. Unlike the majority of western painters who came before him, those who have objectified the female beauty as a representation of sexual desire and fantasy, Haure emphasizes that the Balinese are indeed human, and a reflection of ourselves.

“I represent the Balinese girls adorned in beautiful traditional attire, before or after, yet not within the context of traditional dancing, or cultural activity. I am not searching for the exotic cultural role or the person that is objectified. I wish to capture them in contemplative, personal moments,” the artist says. “I endeavour to make clear distinctions between what is the object and what is the human being. The Balinese female beauty is exotic, yet I believe this is an incorrect observation – it is the objectification first without recognizing the distinctive character of the individual.”

Haure’s introduction to Bali and his integration within the culture is unlike any other foreign artist who has come before him. Born in 1969 in Orléans, a city in north-central, France, in 1983 he entered Ėcole Boulle de Paris, the institution renown for emphasizing creativity and expertise, and training the finest craftsmen in the country. Upon graduating with a diploma of "métiers d’art" in 1989, he was employed on a government project in the restoration of French national furniture.

Devoted to Catholic Benedictine religious beliefs, he joined the monastery of St. Benoît sur Loire also in 1989. Soon after Haure was posted to Indonesia and assigned to the Sasana Hasta Karya School of Art in Gianyar, Bali, and here he lectured on cabinet making, drawing, painting and the operation of machinery. Haure developed a passion for black & white photography in 1992, which balanced and enhanced his artistic pursuits. Four years later he assumed the role as the headmaster of Sasana Hasta Karya while living in the Abianbase Royal Palace, becoming a member of the Palace musical group, Bala Ganjur.

Dedicated to honing his drawing skills Haure began regular anatomy classes at the Pranoto’s Gallery in Ubud in 1997. In the same year, he exhibited paintings in his first exhibition in Jakarta at the Hilton Hotel. From then on he showed in-group, and solo exhibitions in Bali, Jakarta and Singapore, and he was represented by Bamboo Gallery in Ubud, Bali from 2001. A career highlight for Haure was receiving the First Prize in 2016 for his painting Melancolia at the internationnal salon de Taverny, France.

The Creative Process

Upon our first observation of Haure’s paintings, a question immediately comes to mind – what is it that the artist is trying to express? Close inspection reveals the flowing contours of multiple, harmonious and contrasting pigment washes on paper, and upon this dynamic milieu, the artist sketches his Balinese characters. Watercolour, acrylic and colour pencil backgrounds meet with the pure lineal power of the graphite drawing on top. He begins the work by applying the background, and this then dictates what and how his figures may be applied.

Haure’s challenge is to make the intricate compositions visually cohesive within both its realistic and abstract elements. Special attention to balancing blank white areas of the paper with random colourful shapes, fine pencil lines with stronger, thicker contours are required. Haure’s creative process is purely intuitive, with each part of the painting requiring different technical attention to complete the details.

“I have to be adaptable to every part of the creative process and the construction of the picture, changing colours from lighter to darker or contrasting, from thicker to thinner lines as well. The creative process demands me to go in deep and investigate,” Haure states. “Beauty has to be searched or explored and not elaborated!”

- Jean-Philippe Haure, Duality VI, 2008, water media on paper, laid down on canvas, 73 x 54.

Inspired by classical beauty and the European master painters Haure is primarily influenced by the Dutch draftsman and graphic artist Willem Gerard Hofker (1902-1981) who travelled the Dutch East Indies archipelago and settled on Bali in the 1930s. His distinct paintings reflect his understanding of Bali and its potent physical and non-physical worlds. The beauty and humanity of his Balinese characters, along with the mysterious elements that emanate from the backgrounds are immediately intriguing, and rarely do we have the opportunity to observe works of such unusual, eye-catching quality. Jean-Philippe Haure follows his heart in the pursuit of elegance and visible perfection, manifesting pictures that stand alone. He reminds us that painting is perhaps humanity’s highest and noblest achievement of all.

Words: Richard Horstman

This article is published in NowBali, September 2020: