Only a narrow part of what’s perceived is intelligible.

Translated by Paisi.

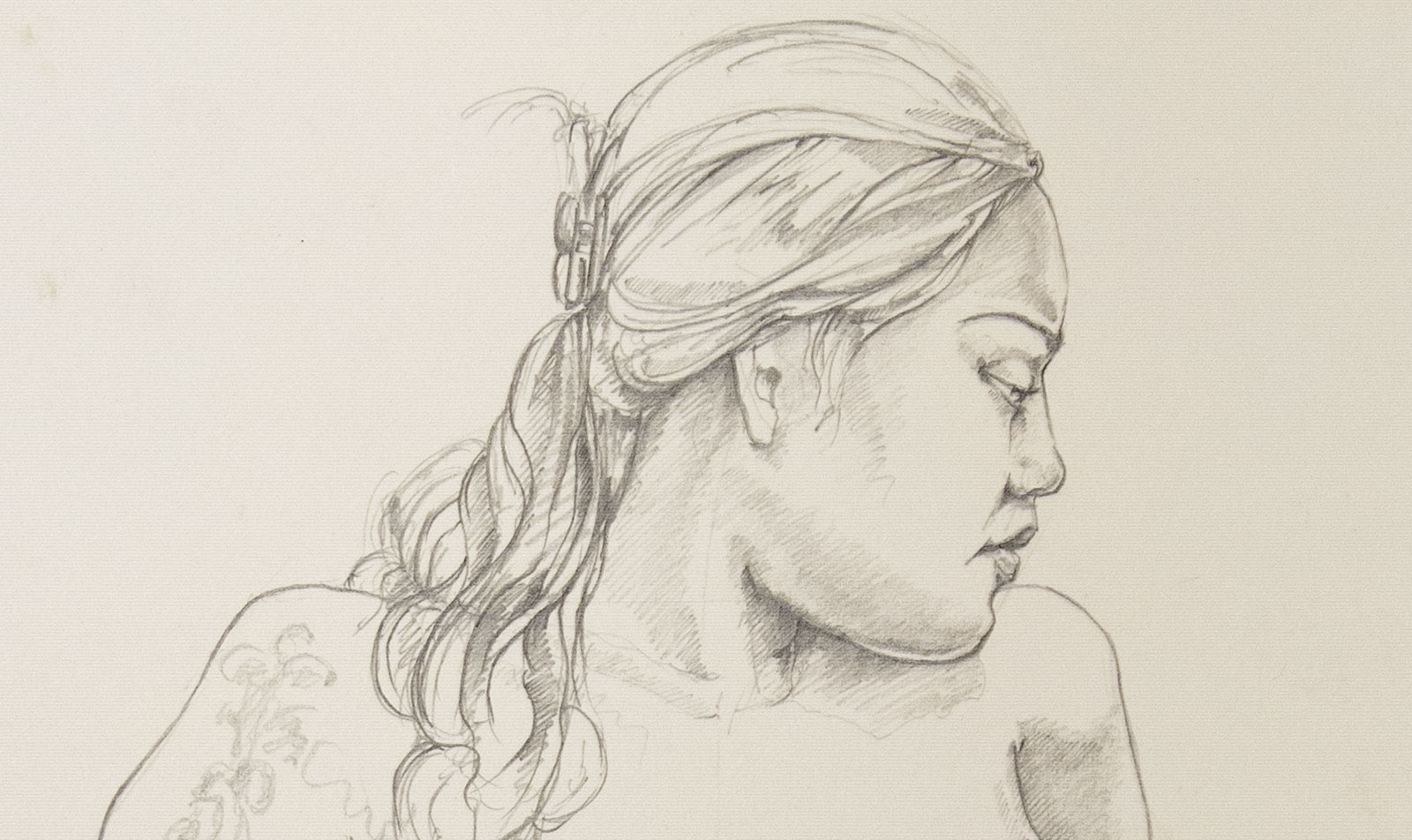

The question of resemblance in a portrait is a delicate one. Coming from a generation born after more than a century of Western de-construction, on all artistic, cultural or literary levels, it is becoming difficult for me today to name the points that make a portrait, a simple sketch of a few minutes or a more elaborate work, be said to resemble the model.

The artist’s quest for resemblance during a live model session, can take place on very different levels, depending on the style or the way the work is done. However, resemblance implies two parallel interpretations: first, that of the artist in front of his model, comparing his work with the model, and second, that of the spectator in front of the artist’s work, also comparing with the model.

But let us leave aside the second interpretation to try to understand the first, that of the artist in front of his work.

Where indeed is this resemblance that he is trying to translate? Looking in turn at the model and the development of his work, adding lines and colors on the support, forcing a contrast here, erasing a “mistake” there, in short, he is working nimbly on a flat surface. But there is no connection between this worked flat surface and the living model. Nothing is similar: a face against graphite lines, light against an touch of gouache, a rhythm expressed by a few directed hatchings, a physical color against a surface of manufactured pigments. Nothing is comparable. And yet it’s all there. The model is there, framed by the edges of the paper, and what’s more, it looks alike…

A paradox emerges: it is impossible to see the resemblance independently of the lines and colours that express it on paper, and at the same time, the resemblance is not just this combination of lines and colours. So where does it lie? We could say that the resemblance lies in the artist’s intention, in what he saw of the invisible order and was able to translate: this character, this accuracy, this indefinable "truth". What he saw was a space between his work and his model. And all his work consists precisely in making visible what is not, in making more explicit what is sensed without being able to express it, and which is hidden behind a face, a life, a model. This is why a portrait made by an artist can be felt more real and more true than the model itself. Through a kind of creative alchemy, the portrait reveals the meaning hidden behind appearances.

On the level of the language of forms, many so-called “non-resembling" portraits are closer to felt reality as to the impression that emerges from the portrait, which is "more itself than the model". We can say of this portrait: That’s him! However, design-wise, not a single line or color conforms physically to the model. "Him", transposed into the language of forms becomes "It’s him". Here the interplay of colors and shapes gives birth to life. Often even unknownn to the artist self. How can this life be captured? The artist’s technical ability, sufficiently practised to avoid all sorts of clumsiness, failures or aesthetic errors, will be put aside, as if muted, to position himself in a kind of presence in the world, hovering over it or taking a step back, which becomes capable of capturing and translating this impression, as if without taking possession of it. The artist’s presence in the world is a kind of absence from oneself. A kind of distracted presence to oneself that allows one to be present in the world…

This is the opposite of the scrutinizing, possessive gaze that is captured by the tools of objective analysis, more suited to dismantling than to the search for meaning, giving us to see something like the parts of an engine spread out on the floor of the mechanic’s workshop. This dismantling, whose novelty is often very attractive from an artistic point of view, very similar because of its dismantled and demonstrated parts, disregards all the links between the parts, all the articulations of the visible that give us in transparency a view of a meaning that can finally be grasped by our intelligence. This dismantling, from which our Western age has emerged, makes appearances disappear, and consequently, access to the invisible that the artist perceives fleetingly. Appearance is the condition of being of the invisible. What is intelligible is never more than a tiny part of what’s sensible.

“For my taste, these modern Actaeons boast too soon of having discovered the secrets of Beauty: must it be, because we have analyzed the rainbow and stripped the moon of its oldest, most chaste mystery, that I, the last Endymion, should lose all hope, because impertinent eyes have leered at my mistress through a telescope?” [1]»

It is only after the fact, or through the judgment of another, that this work, often obscure during its execution, will reveal itself to be “more itself than the model itself”, resembling, as for the impression that emanates from it, the in-between of reality, the space between the sheet and the model, captured and translated as if by accident.

I remember an art teacher at the École Boulle, who, during a live model session, told the students we were then to: "never throw away a piece of work".

Today, I feel that among all these drawings piled up in a corner of the studio, is perhaps hiding the possibility of that glance afterwards that could reveal an in-between, captured nonchalantly and ignored until now.

These might be lofty thoughts for just a few lines and colours on a sheet of paper. However, when this resemblance becomes a research spanning years and most likely never completed, it deserves a few lines that live up to its expectations.

So,

I draw

You draw

He draws

We draw

By design.

Please note

[1] Oscar Wilde, Le Jardin D’Eros. Traduction et Préface par Albert Savine.