There are innumerable interpretations of Bali, a place where the past and the present often meet uneasily. The Island has long attracted a great diversity of artists. Figuration and abstraction, reality and dream have come alive through their work in myriad beguiling narratives that reveal a complex society.

The French artist Jean-Philippe Haure makes paintings that are restrained narratives of Balinese people, places, and spirit. At first glance, his art appears fragile, as if a puff of wind might wipe color and line from the paper in an instant. But his art is not fragile: it has the linear strength of a robust marriage of color, geometry, and subject that delights the eye and stimulates the imagination.

Haure has discovered beauty’s grace in myriad places: in dance, in causal glances, among the impoverished, in a moment of anticipation, in an intimate touch, in the emaciated form of a solitary man, in the midst of a festival, and in abstract dream. Haure is not obsessed by the toughness of contemporary society or the constraints of community traditions; rather he demands that we look closer at the dispossessed inviting us to see the unique grace of the survivor. His observations force us to take note of the inequalities that blight society. But painful realities are set off against the elusive ritual of the festival and elegant women, finely coiffed and clothed in striking traditional dress: they are beguiling presences in the deep quietude of a timeless culture.

The journey into Haure’s figurative and abstract Balinese world begins not with a subject or questions of aesthetics but with hued wash: the work flows from this base. “For me, the wash is very important. This is where the story starts,” he says. “When I see an ‘everyday-life-model’ in the street, it motivates me to work. Any questions on aesthetics should be found in the wash first.”

Even as Haure’s oeuvre deals in the meeting of fantasy and reality, he captures something of the spiritual nature and the studied pace of Balinese life. He brings elements of wonder to his tales, small dramas possessing a singular understanding of his protagonists, refined through years of observation and living in the community as a teacher. His subjects are brought to life through a soft color palette and abstraction that “whispers” to viewers’ emotions in such intimate works as After the Bath (2006), Colors From Indonesia (2006), and Melancholia (2013). Haure’s palette also lightens the austerity of his stark figurative works such as The Time Keeper (2012), Stay Alive (2012), and Keeping in Mind (2014). The results are varied dreamlike experiences that linger in the mind’s eye.

While Haure’s art, for all its color and fine line, suggests the easy accessibility of photography, his painting demands that viewers tease out the heart of his tales, to give life to them beyond the frame and his smooth seductive surfaces. This is vividly accomplished in such portraits as After the Bath (2006), the triptych Duality XVII (2008), Wisdom behind the Age (2011) I’ve Got a Dream to Remember (2012), Wind in the Trees (2012), Stay Alive, I Would Like to See the Other Side (2012), Melancholia (2013), Keeping in Mind (2014) . In this series of paintings Haure speaks candidly of lives lived on the edge of society, personal struggle, age, isolation, sadness, mental anguish, loss, and dreams. Here, for a few moments, we are voyeurs of a surface calmness but aware, too, of personal angst. There is no torment in Wisdom behind the Age but there is sadness in the face and eyes and posture of the elegant, handsome woman with her furrowed brow, here right hand clasping her knee and the fingers of her left hand pressed to her head, her voluptuous breasts almost tumble from her dress. Her eyes look at us but she does not see us: one senses that she may be looking back to her youth, to time when her beauty drew admiring glances, a time when she pampered herself just as the sultry young woman in After the Bath does. There is quiet pleasure here but not in Haure’s moody painting Melancholia, on the other hand, in which the young woman gazes without focus at the ground, her hands on her feet. Her sloped shoulders and absentminded gaze speak to the sadness that grips her mind. Haure realizes these three women in subtle line, exquisite detail, and abstraction that seems to rise as a living entity from the ground emphasizing the natural eroticism. In the triptych Duality XVII, however, the old woman— arms at her sides, face stern, and eyes curious with questions—gaze out at the world resigned to her fate. One sees quiet dignity in her cracked, fading beauty, but it is beauty nevertheless, not a false narrative, which makes many uncomfortable. “We are afraid of beauty,” says Haure. “We are terrified of beauty as a torment [for it is] excruciating, unreachable. I want to capture the precise moment when things are exquisite.”

Haure’s I’ve Got a Dream to Remember; Wind in the Trees; Stay Alive; I Would Like to See the Other Side; and Keeping in Mind are excellent psychological studies of men alone, solitary figures who, through their postures, suggest resignation to life’s troubles. Either squatting or standing as they work or rest, facing us or with their backs to the viewer, we are aware of their abject struggle to be. They are surviving in hard times, eking out a living as best as they can. Haure brings each figure alive through well-placed wash and muted colors, which recalls the free expression of tachisme. Haure’s descriptive line reveals layers of his protagonists’ lives.

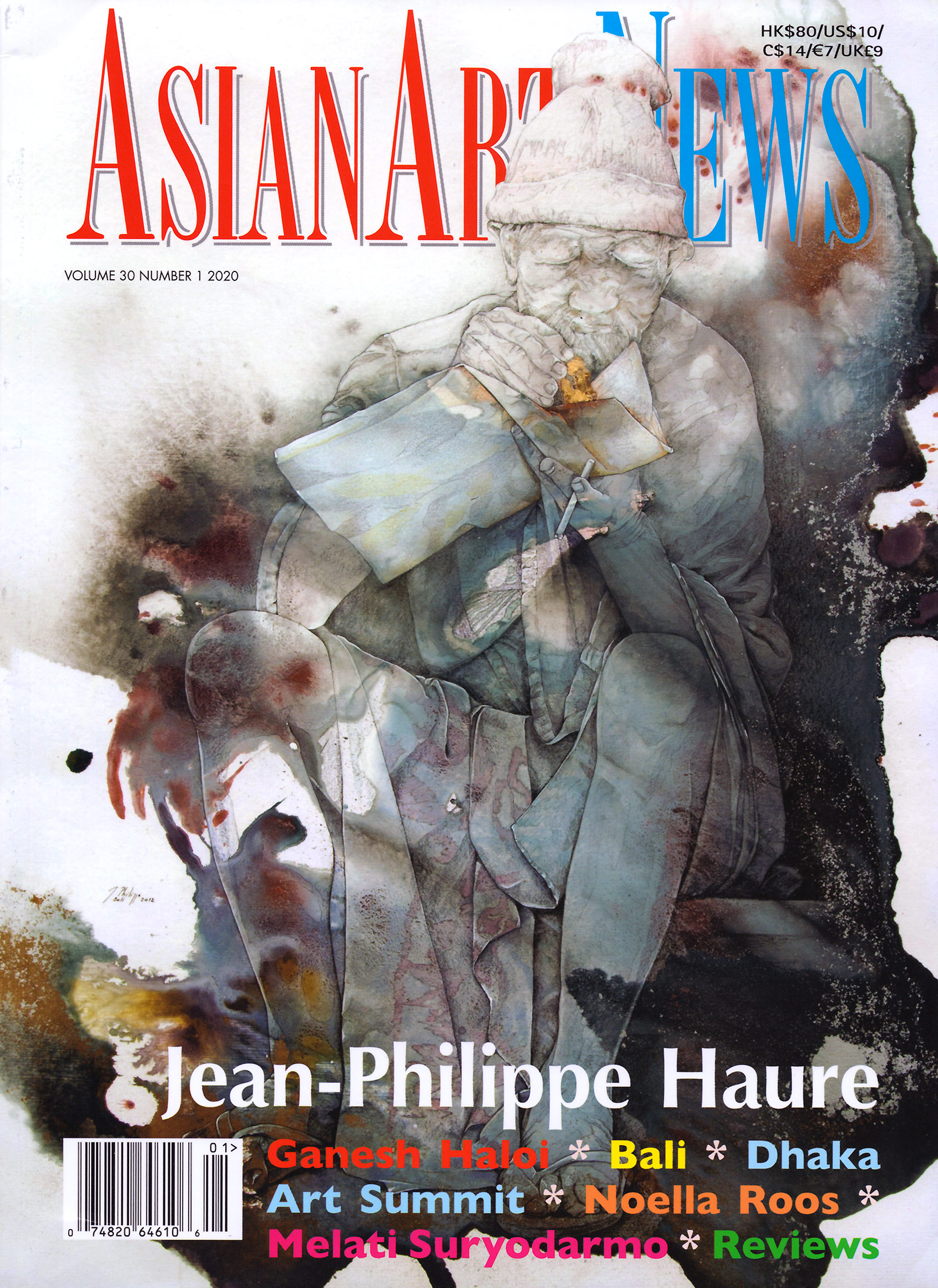

There is something restrained, too, in Haure’s presentation of male figures whose hardscrabble lives he portrays. Here is impoverished humanity captured with grace and respect: there is neither romantic nor nostalgic idealization of the figures. Here an elegant line and abstract washes combine toughness and gentleness that surprises. A tender memory is revealed by a hand placing a single flower in I’ve Got a Dream to Remember and in I Would Like to See the Other Side the man looks longingly into the distance where he can only imagine another life. But for me, Haure’s three most powerful and sensitive figurative works are Stay Alive [see Cover], The Time Keeper, and Wind in the Trees, which are beautifully realized paintings of understated human torment.

The wizened figure of Stay Alive is androgynous, the crunched-up face speaks to time’s deft aging touch; his right-hand fingers lift a morsel of food from a paper holder to an eager mouth; the left-hand fingers hold cigarette. Sitting on his abstracted place it looks as if the earth and he are one. Haure’s details of the face, hands, fingers, feet, and toes as well as how his clothes fold reveal his body add to the character’s presence. The strong lines of the bones washed with muted hues of burnt browns and reds and purple lend the body of the man in The Time Keeper a sense of despair, reinforced by the folds of his ragged clothes. In the wrinkled skin of the aged face eyes stare out in the middle distance as if his thoughts are perhaps of once-pleasant memories now lost in the doubt of the present. The burning cigarette gripped loosely between thin fingers punctuates his thoughts.

The sense of despair in Haure’s portraits of the impoverished is perhaps most vividly caught in the bent, emaciated figure leaning slightly forward in Wind in the Trees. Again a combination of strong and delicate line and light-colored hues define character and place. That Haure’s portraits have, at times, the quality of photorealism is no accident as the artist employs photography as a tool and as a reference point in his art-making. As the Bali-based critic Jean Couteau notes on Haure’s astute use of photography in his essay The Art Concept Rhapsody (2012): “Photographs … contribute the lines, and eventually, the ideational content of the work. But how can a photograph do this? By lending only some of its lines, the most evocative ones, while letting go of any overly narrative, detailed content. Of the photograph, there will eventually remain only the minimum needed to suggest a scene, and through this scene, a certain understanding of sensitivity, tenderness and love. Everything is suggested rather than affirmed. As a flowing mood then runs beyond the colors into the lines of the sublimated real.”

Regardless of how transient Jean-Philippe Haure’s world may appear, it is one established on keen observation and deep Christian faith. Born in 1969, in Orléans, France, on the banks of the Loire River, Haure studied arts and crafts at the École Boulle from 1983, which was where, according to the artist, “I discovered the love of work well done, the techniques to achieve it, and the way to develop one’s own personality and creativity, all based on the knowledge of art history, not only theoretical, but applied in the workshop. I felt that something was missing: the philosophy of art. I wanted to understand what art is. I went to the Sorbonne and audited courses. I studied Idea, by Erwin Panofsky that opened the door of philosophy for me.” This was followed, in 1989, when he became a monk at the Benedictine monastery of Saint Benoit sur Loire where, as he notes, he learned to “dive in the silence, this is what I started to learn in the monastery. I feel very close to this life.”

In 1990, Haure arrived at Sasana Hasta Karya School in Bali, as a volunteer, where he has taught a broad curriculum. Bali and its culture have, over the past 30 years, become an integral part of Haure’s artistic vision whose sensitivity to his Asian subjects reminds one of that of the Japan-based French woodblock artist Paul Jacoulet (1896–1960), especially with his individual figuration. But Haure’s art is also touched by the rich spirit and techniques of a wide range of artists including Edgar Degas (1834–1917), especially the freedom of his pastel drawings; the academic and romantic orthodoxy of Ingres (1780–1867); the courage of the free life without compromise of Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), the Balinese figuration of Willem G. Hofker (1902–1981), and the charcoal drawings by the Singaporean artist Teng Nee Cheong (1951–2013). Such artists have taught him that he stick to one place to examine it closely, for as he says, “I prefer to go deeper in the same place than travel around to discover every ‘lieu commun’ of each place. I don’t like the surface, I prefer diving.”

But even as he is in one place, Haure’s vision is not rigid. It is full of the spice of life and not clichés. It is full of the spirit of adventure that sent him on his voyage of discovery so many years ago and one that has always remained with him. As he says, “I had a chance to move [from France] to discover a new culture. Almost 30 years of living in Bali teaches me how relative a culture is. The universality of beauty removes them. I am happy to be born after the European modern history of painting. I get freedom from all these painters. They freed the language of forms. But for me, they did not go far enough. Learning how to make chaos is one thing but being aware of the beauty that appears in that chaos is another.”

Haure’s secular and spiritual life nurtures his reflective nature, where silence and action are singularly united. He sees dignity and beauty in simple intimate scenes just as he captures alienation among the poor and a timeless beauty among the privileged. But he does not judge, rather he allows his lyrical abstraction and figuration to guide us on his artistic journey. One sees this in Waiting for the King (2018), which is a pleasant scene of two boys waiting expectedly for the King to pass by. The luxurious designs of draped fabrics speak to Haure’s love of color and abstraction, but it speaks to the intimacy of the still moment, too, as in Colors from Indonesia (2006) where a beautiful girl leans forward to touch her foot gently with outstretched fingers and Coral Reefs (2019) where a young woman with her back to us is swept up in pensive mood. Haure builds tension in this work through the muted colors and wash of her dress and such physical details as her outstretched hand and a bent foot.

The accessibility of Haure’s art is refreshing as is the ethereal quality that transports viewers into very private worlds. It is in the richly colored and romantic dream-like Gemini (2004), where the dominant rich blues and muted reds and the flowing line add to an unusual tension. The lavishly detailed and colorful festive group in the work entitled Unless You Know Another Way (2020) reinforces the dream-like character of Haure’s art, as does the dramatic abstract-figurative work Duality XIII (2008), an unusual union of human and animal contact in his art. This is in stark contrast to the personal moment of the two women of Duality II (2006) and the single female in When Grace Abounds (2010). There is a striking hint of the English Pre-Raphaelite ideal of beauty in these works—and many others—that carries Haure’s dreamy abstract narrative along, and though they are touched with the sense of romance they are, at least to my mind, not sentimental. “Abstract painting is stronger than any other paintings in emotion, and drawing that is also stronger than a finished work. I mix these two techniques together,” he says. The results, as we see, are deeply appealing.

Among Haure’s most beguiling works is the diptych such as Both Sides of the Story (2011) and the triptychs such as Duality XVII (2008) and Duality XIX, Waves in the Sky (2011), which is a dream. [The model for all the figures is Haure’s wife, Reizka.] These works speak to Haure’s secular and religious sides. The secular is the everyday narrative, formal and informal, of the people portrayed. And in the manner in which the works are framed, the panels suggest religious altarpieces found in numerous Catholic churches. Haure’s artisanal skill and attention to the detail in the making of the panels is something he achieved during his studies at École Boulle almost 40 years ago. In these works there are very human and personal dialogues taking place in subdued settings that recall old sepia photographs, where his wash suggests time past. Looking at his figuration here, one has a sense of the narrative extending far beyond the edge of the paintings’ frames as one finds in religious altarpieces of biblical scenes. The entire work is a complex narrative journey of which we have but a glimpse, making viewers voyeurs of private worlds.

One may be looking for a message in Haure’s works but as he says, “I have no message. I don’t want to change the world, only to fight to keep my art alive. I am not judging the world or people in my art. The only thing I can say is ‘I want to see the other side.’” The world now, he notes, has become a place where everything has become “an object for commercial purposes, human life included. If I touch some kind of truth, by accident, emotion, beauty, spiritual connection, or love will come alive. It is the consequence of my actions, not the intention.”

And as for the feeling of mystery in his vision, his mixedmedia materials lend themselves to this. But it is not something that Haure goes out to do, for mystery is not created by the brush or a pencil, it emerges of its own accord as the artist works.

“I can’t say that I wish to do something in my art,” Haure says. “What I do is prepare the conditions, specially for the wash step, where some ‘event’ may happen. I mean a form of language even. Using all the tools I have (colors, texture, lines, contrast, balance, harmony), I put everything together in a kind of chaos. Sometimes, something unusual appears, a new ‘music’ in the language of forms can be heard. I need to be careful. It is so easy to destroy it by adding my own will to it. If I use my will, I fail.”

Jean-Philippe Haure’s search for beauty is ongoing, something that will insinuate itself into all his art. The search for beauty is a tough taskmaster for it demands everything from the artist’s personality and skill, vision, and spirit. As Haure says, “Beauty is a place to rest, and is not joyful. Sometimes it provokes a fright that makes us move away. It’s the appearance of the ineffable, the language of the unspoken. Beauty accepts no compromise. When working on my wash and trying to make the model appear clearly, I have to make so many decisions (choosing lines instead contrast, changing the color or the saturation, using a wash texture as a figurative part, adding a white line, covering an area, erasing some details, and so on. I think that all these decisions, when added together, have an uncompromising effect. Paintings that are not successful have hesitation and mawkishness.”

Haure sees his world forever on the move. In his art he seeks to reach out beyond the surface to describe a Bali that is rich in spirit. As he says, “The world we don’t see always reminds you of the magical, ceremonies, rites, sacrifices, offerings, beauty and fertility.” In any search there are surprises and delights, successes and disappointments. Jean-Philippe Haure’s embrace of the search for grace is filled with these, which is why his art is deeply individual.